advances in grilling for one

When I was a kid, my older brother and stepdad rigged up a barbecue grill the way good old boys all over Texas did: They got their hands on an empty 55-gallon oil drum, cut it in half lengthwise, added hinges and legs and cut a grate to fit inside.

I remember the grill being black as night, but I’m not sure whether they had painted it that color or that was just the “seasoning”: smoky grime from all the beef briskets that had melted into tenderness over the smoke of smoldering wood and coals.

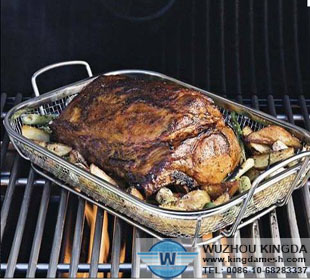

Like pit masters tend to do, my brother, Michael, cooked for a crowd on the thing, whether a crowd was gathered or not. A family of six can get a few good-size meals out of a brisket, it turns out.

I ate my share of barbecue in my youth, especially once I got to college and would meet my brother for some lessons in evaluating top-notch brisket, ribs and burnt ends in the best joints around our homes in Austin and College Station. I didn’t start tending my own Weber-made “pits” until I moved to ’cue-less New England, but I had internalized some of the most crucial lessons: that Texas-style barbecue is about smoke, not sauce; that low and slow means you have to be both attentive and patient; and that fat carries flavor.

I sold or gave away my grills (yes, plural), a little bullet smoker and the outdoor space that held them when I moved from Boston to the District in 2006, and it took me a while to get a little of my grilling mojo back. Last year, I ended up buying a spiffy red Aussie Walk-A-Bout that’s meant for wheeling from one spot to another, hence the name, and shared custody of it with a friend in my co-op building (also named Michael, coincidentally). Once, for a casual party with some friends from the dog park, Mike started things off by filling it with so much charcoal that the paint melted off the underside, which glowed from the heat and scared us to death. I had to pull out half of the coals before I could even safely put anything on the grate without subjecting it to the equivalent of lightning. I also fed visitors to the open house at the a community garden where I had a plot, grilling shrimp that I skewered with sturdy rosemary branches from the garden.

One thing I never did was use it to grill for myself, mostly because it just wasn’t convenient. To do so, I’d have to fetch it from my basement storage unit, trudge it outside to the sidewalk or courtyard, and spend far too much time ferrying plates, tools and food back and forth from my fourth-floor apartment. I might as well just turn on my oven’s broiler and throw some smoked paprika onto the food to bring the outdoor flavor in.

Nowadays, I’m cooking with fire again. Inside my sister and brother-in-law’s homestead in southern Maine, where I’m living this year, the main source of heat is a beautiful Stanley cookstove that, November to April, is also the preferred vehicle for meal preparation. Outside, a beehive oven gets fired up from time to time for pizzas, then bread, then roasts, beans and vegetables as the heat dies down. Low and slow.