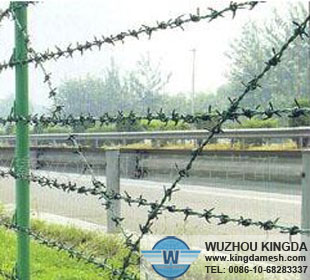

the father of barbed wire

A street in Metairie is one of the few reminders of William Edenborn. One of the country’s richest men, the father of barbed wire, the builder of what would become U.S. Steel, Edenborn moved to Louisiana late in life from St. Louis to follow his “hobby,” which was building railroads.

Born in 1844, Edenborn was orphaned at 14 and came to America after apprenticing as a wire maker. He moved to St. Louis and began making wire, tinkering with machines that could replace hand-drawn methods, just at the time the West was opening. Within two decades, he was one of the richest men in the country.

Edenborn did not invent barbed wire, but in 1883 he patented the machine that slashed the cost of making it. He bought up wire makers who could not compete with his price and controlled 75 percent of the market. He also patented many kinds of barbed wire, including his famed “humane” wire, with smaller, duller barbs, that convinced ranchers to start fencing in their lands. At the end of the 19th century, he sold out to J.P. Morgan for $100 million, and U.S. Steel was born.

After getting out of the wire business, Edenborn began building what would become the Louisiana and Arkansas Railway. When the first stage to Shreveport was opened in 1907, he moved to Louisiana, splitting his time between a relatively modest home on Hampson Street in the Riverbend area and a farm in Winn Parish. He assembled a railroad that grew into the Kansas City Southern. Despite his wealth, he lived frugally on just $200 per year, or about $5,000 in today’s currency

His Louisiana and Arkansas Railway linked New Orleans to Shreveport and eventually pushed into Texas. With a million acres, he became Louisiana’s biggest landowner and oversaw a vast cypress logging operation.

A native of Germany, Edenborn was a leader of the state’s large German community during the polarizing days of World War I. He urged German immigrants to support the American war effort, but he ran afoul of the patriotic fervor of the times by defending the loyalty of German-Americans.

With wartime passions running high in 1918, Edenborn spoke at a Liberty Loan rally for German-Americans in New Orleans. His defense of German-American patriotism and a veiled swipe at the British raised ire among anti-German watchdogs. He was arrested, with a lynch mob waiting for him. But tempers cooled, the war ended and Edenborn was never indicted.

Edenborn died in 1926; his wife moved back North and sold her Louisiana holdings.